Over the past 10 days a renewed Russian offensive has pushed the Ukrainian armed forces out of the area they captured in a lightning offensive back in August. This collapse of the Kursk salient marks an end to a 7 month operation that drew both high hopes and harsh criticism.

What has happened in Kursk over the past two weeks? Why were the Ukrainians forced to withdraw their forces from the salient? What does the loss of Kursk mean for the larger war effort and what will the Russians do next?

The long march to March

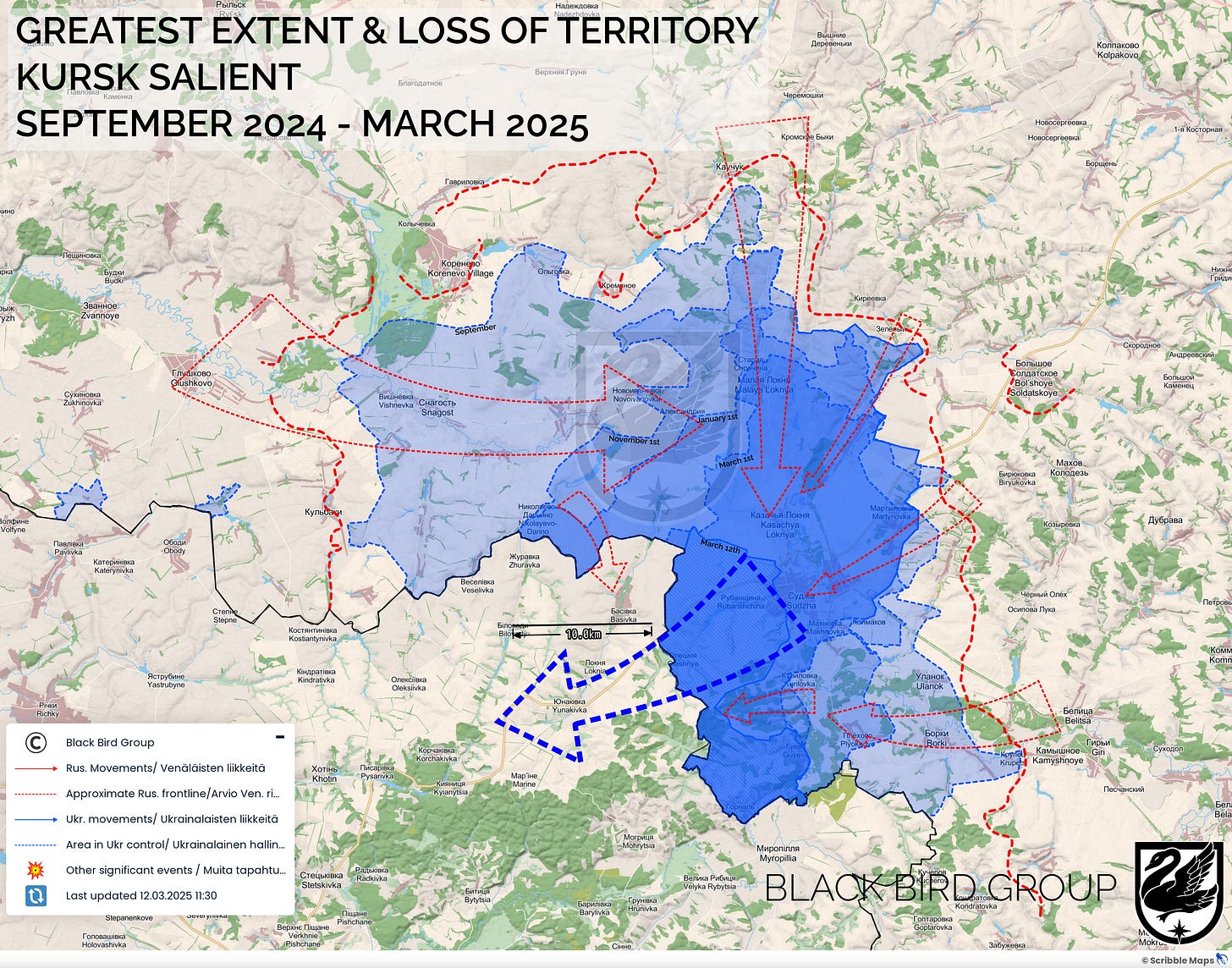

In August of 2024 the Ukrainians executed a surprise offensive into Russia’s Kursk Oblast. Suffering from manpower problems, losing ground in the east and the discourse around the war turning towards peace negotiations, the operation was likely drawn up as a way to ease the pressure Ukraine was facing.

As stated by Ukrainian officials, the goals of the operation were to draw Russian forces away from the city of Pokrovsk in Donetsk, occupy Russian ground to be used as a leverage in future peace negotiations, and spoil a possible Russian cross-border operation from Sumy. It’s likely that, if successful, the operation was also meant to create pressure on the western flanks of the Russian grouping in Kharkiv, and generally raise morale and shift international discourse away from the eastern front where Ukraine had been slowly losing ground for months.

The initial days of the operation looked promising. Ukraine caught the Russian troops on the border apparently by complete surprise and managed to capture over 1200 square kilometers of Russian territory while taking a large number of prisoners.

However, cracks soon began to appear

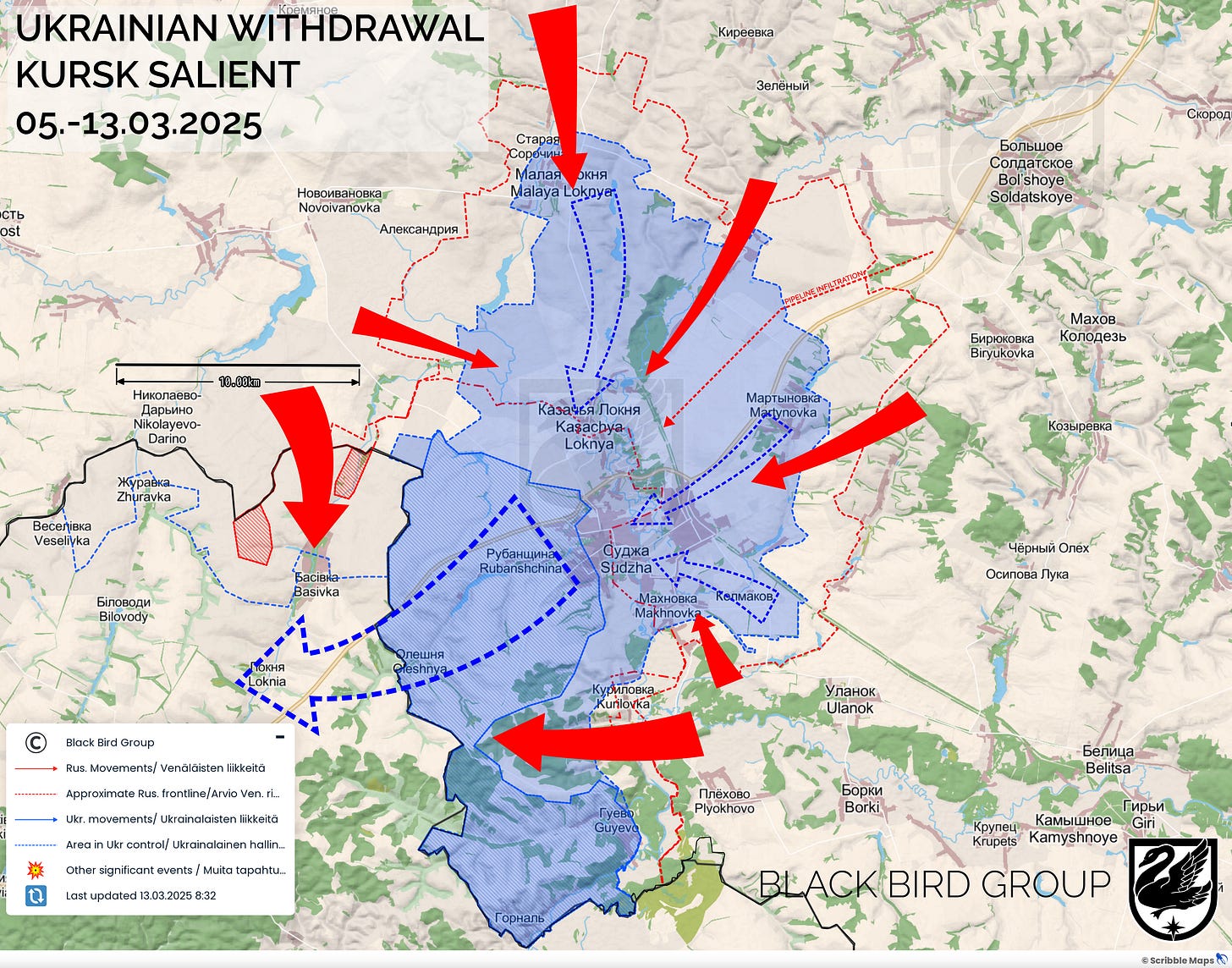

Ukraine failed to expand and secure the flanks of the Kursk perimeter, and as Russian reinforcements kept trickling in, the Ukrainian operation turned to a defensive one. Over the next half a year the Russians would significantly reduce the Ukrainian perimeter in Kursk. By the beginning of March 2025, the Ukrainians found themselves still holding onto a narrow salient some 15 kilometers wide and 30 kilometers long. With the latest Russian advances narrowing the mouth of the salient in February, the Ukrainian position in Kursk had become untenable.

Collapse was just a matter of time.

Bottleneck to Sudzha

The Ukrainian perimeter in Kursk was tied to the Sumy oblast of Ukraine by a narrow lifeline made up of two roads. The larger one of them, the main supply route (MSR), running from Sumy to the town of Sudzha through a Ukraine-Russia border crossing, and a smaller one, the secondary supply route (SSR) a route running over fields on the Ukrainian side of the border, and then joining a road on the Russian side of the border south of the village of Oleshnya

.

Although the Russian rate of advance in Kursk had slowed down, they had continued to capture ground on the south-western flank of the perimeter. In February the Russians took the village of Sverdlikovo situated on the Russo-Ukrainian border and crossed the border to move towards the villages of Novenke and Basivka. The steady advance meant that Russia had created a bottleneck at the base of the salient.

From Sverdlikovo the Russians could constantly fly drones over both of these routes, creating what can be only described as “Kill Zones”, where a large amount of Ukrainian equipment was destroyed. This made the supply of the Ukrainian salient nearly impossible. Worse yet, the mild winter conditions had made off-road movement for vehicles extremely challenging.

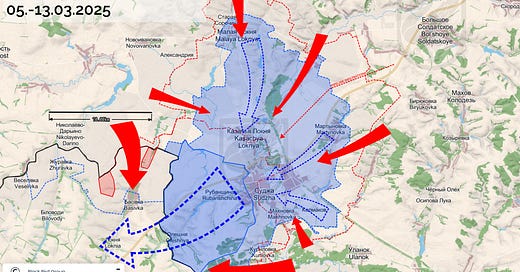

Meanwhile on the eastern side of the salient, the Russians had created a minor bridgehead over the Psel river south of the village of Kurilovka. On Wednesday the 5th of March the Russians started expanding this bridgehead and launched an attack westwards towards the SSR.

According to Ukrainian sources, the forces used in this attack consisted of at least two battalions of North Korean troops. While these claims sound plausible, as of the publication of this article we have no hard evidence of North Korean involvement in these attacks.

By the end of Thursday, 6th of March the Russians had severed the SSR leaving the MSR as the only route out of the salient. The situation had become critical. If the Russian advance west of Kurilovka continued, and especially if it was met by a similar attempt directed towards the MSR from Sverdlikovo, the whole Ukrainian contingent still in Kursk might become encircled

The Ukrainians drew their operative reserves to counterattack the Russians advancing on the southern side of the perimeter. While the counterattack seems to have contained the Russian advance, it doesn’t seem like it managed to push the Russians backwards, leaving the whole salient vulnerable.

The North Collapses

The attack in the south was likely meant to be a part of a coordinated killing blow to the Kursk salient. Almost as soon as the southern attack had severed the SSR the Russians launched a renewed attack on the northern half of the salient all around the perimeter from the village of Malaya Loknaya all the way to Martynovka. The Ukrainians soon began to withdraw from the villages on the extreme edges of the perimeter, making their way towards Sudzha and the village of Kazachya Loknaya.

To the south-east of Sudzha the Russians also went on the offensive, but it’s likely there was less advance here and these attacks just likely tied up Ukrainian forces on this sector.

While there are some indications that the Ukrainians had rotated some of the more experienced units out of the Kursk before the start of the Russian offensive, it’s very unlikely that the Ukrainian withdrawal from the north was a planned maneuver. At the very least the Russian offensive disrupted any plans for withdrawal. However, some of the more important units, such as drone pilots, were prioritized in the withdrawal, which then made the situation more difficult for the remaining forces.

In the Ukrainian rear the Russians struck the remaining bridges over the Loknaya, Sudzha and Psel rivers, leaving the Ukrainian forces stranded on the far side. Some of the routes were also blocked by damaged Ukrainian equipment. This mean that the Ukrainians units had to make the grueling journey back to Ukraine on foot, some marching over 30 kilometers over multiple days.

Russian milbloggers published footage of Ukrainian forces withdrawing in tight columns of platoon to company size, clearly prioritizing speed and efficiency over protection from the drones flying overhead.

Other footage showed dead Ukrainian soldiers and captured equipment, including an M1 Abrams tank that had reportedly been taken relatively intact in Malaya Loknaya.

Testimonies from soldiers who made it

back to Sumy and Ukrainian bloggers indicate that the withdrawal had been chaotic, and at best loosely coordinated. It’s likely that the initial order to withdraw was made by the local commanders after the situation in the salient started to deteriorate, and the higher echelons only reacted after the withdrawal was well underway.

Pipeline bandits

As a part of the northern offensive the Russians infiltrated a group of soldiers into the Ukrainian rear through an abandoned gas pipeline running through the battlespace. The soldiers emerged from the pipeline in the middle of a field north of the town of Sudzha and south of the village of Ivashkovskii. They soon moved southwest to take up positions in the forests surrounding the railway in the area.

Video evidence shows the Ukrainians hitting the Russians with cluster munitions, but the fate of the infiltration force is somewhat unclear. The Ukrainians claim that the Russian operation failed and the infiltrators were completely destroyed, while the Russians claim that despite some casualties the infiltration force moved south towards the industrial area NE of Sudzha, as well as north to capture the village of Kubatkin near Kazachya Loknaya. These maneuvers would’ve made the withdrawal of Ukrainian forces from Malaya Loknaya and Martynovka significantly more challenging.

It’s also unclear how large the Russian infiltration force was. Initial reports talk of a company sized force of a 100 or so soldiers, while later the Russian sources have claimed over 400, even up to 800, soldiers involved in the operation. A battalion sized force seems plausible considering the claimed objectives of the infiltrators.

While the Russian force did certainly take some initial casualties, it’s unlikely that the Ukrainians managed to destroy the whole contingent. A lot of footage of the troops within the pipeline was published soon after the operation started, but no footage of dead Russian infiltrators was shown. Thus it’s unlikely that the Ukrainians themselves managed to capture phones and footage from the infiltrators.

It’s also likely that the infiltrators did move north and south along the railway towards their claimed objectives. While it’s still unclear if the force managed to fully complete their objectives, it’s likely that the appearance of a battalion sized force deep within the Ukrainian perimeter further exasperated the chaotic situation in the salient and likely contributed to the decision of some local commanders to withdraw their troops from the extreme edges of the perimeter.

The end of the Kursk operation

Despite the Russian pressure, the Ukrainians managed to regroup and conduct delaying actions around the village of Kazachya Loknaya and the city of Sudzha. This bought precious time for the withdrawing units. The Ukrainians likely managed to hold Kazachya Loknaya at least over the weekend of 7th to 9th of March.

However, by the 11th of March, the Russians had captured Kazachya Loknaya and on the 12th the Russians were filmed with flags in the center of Sudzha. Despite the official Ukrainian claims that Ukrainian forces would not be abandoning Kursk, the salient practically disappeared leaving some square kilometers in Ukrainian hands by the end of the 13th of March. Fighting will likely continue on the outskirts of Sudzha and the border villages for some time, as the Russians wrap the operation up.

Some sources have claimed that the Russian advance was caused by the pause in US intelligence sharing that occurred around the start of the operation. We, however, dismiss that claim. The operation could not have been prepared at such a timetable that the Ukrainians would not have received some forewarning, and we not see such significant disruptions in Ukrainian operations on other fronts.

However, it is possible that the pause in intelligence sharing caused some local disruptions and gaps in situational awareness but not enough to explain the Russian success.

The situation on the ground speaks for itself: the disruption of Ukrainian logistics on a large scale meant that some kind of a withdrawal was only a matter of time. The Russians had also previously had success in creating local penetrations with large scale infantry assaults. The elements that lead to the collapse on had all been seen before, and the lack of intelligence sharing at most exasperated the situation, as did the withdrawal of the most important troops once the situation became critical.

By the end of the operation the most important thing for the Ukrainian war effort was force conservation: how well the Ukrainian managed to save their troops withdrawing from Kursk and how much equipment they could take with them.

The Ukrainian casualties are hard to assess. It seems that the Russians did not manage to encircle or trap a significant part of the Ukrainian force in the northern salient. Published footage, so far, only shows handfuls of Ukrainian prisoners at a time. However, a clearer picture of the casualties will likely emerge in the coming days and weeks.

At least some Ukrainian soldiers have compared the withdrawal to the battle of Debaltseve in 2015.

It’s likely that most of the heavy equipment and vehicles the Ukrainians had in the salient had to be left behind due to the drone threat over the remaining supply route.

It’s likely that the Ukrainians will complete their withdrawal to more defensive positions in Sumy over the coming days and weeks. After that the situation is murkier.

The Russians may keep their forces in this sector and attempt to follow the Ukrainian force over the border into Sumy, further pushing on the attack axes from Sverdlikovo and Kurilovka. This would also force the Ukrainians to keep a sizable contingent of defenders in this sector and prevent them from shifting the withdrawn troops as reserves to the eastern front.

However, the Russians might themselves see more value in shifting their forces to support their efforts in the Donetsk region, but in this case the Ukrainians would also be free to shift the withdrawn troops to other sector.

We believe it’s likely that the Russians will attempt to maintain at least some pressure on the Ukrainian forces in the Sumy oblast, as the Ukrainian troop commitment in Kursk has likely diminished their defenses on the eastern front.

Next time we will continue talking about the Kursk operation, as we discuss whether or not the operation was successful, and if it achieved any of its goals.

Nice read, also I must point out 2 things: Gerasimov Said they've captured 430 Ukrainian Soldiers in Kursk , and POW numbers aren't something you can lie about. Depending on the size of the troops present in kursk at the time of collapse, can we make a educated guess on the casualties and difficulty of evacuation? Considering that Putin himself said, Ukrainian Soldiers in the kursk salient have only two options: Surrender Or die